The following history is based upon the British government's

1842 report of the "Children's Employment Commission" by

Commissioner Mitchell.*

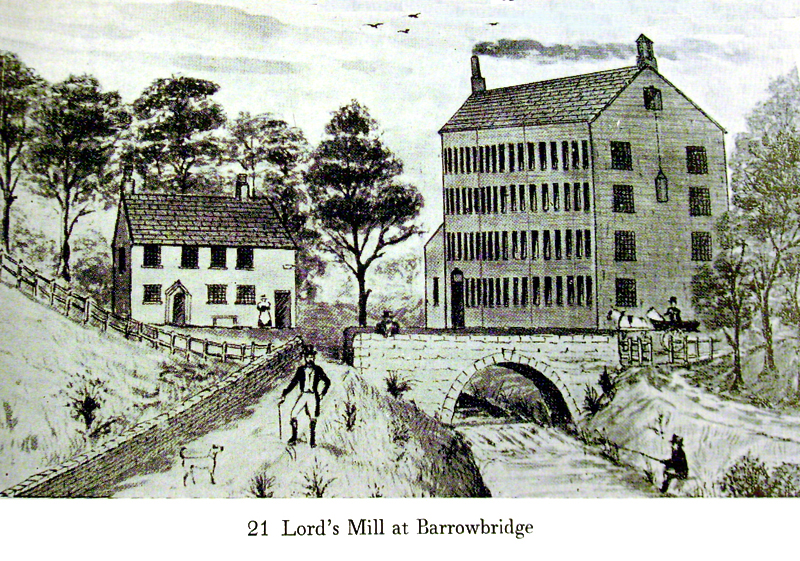

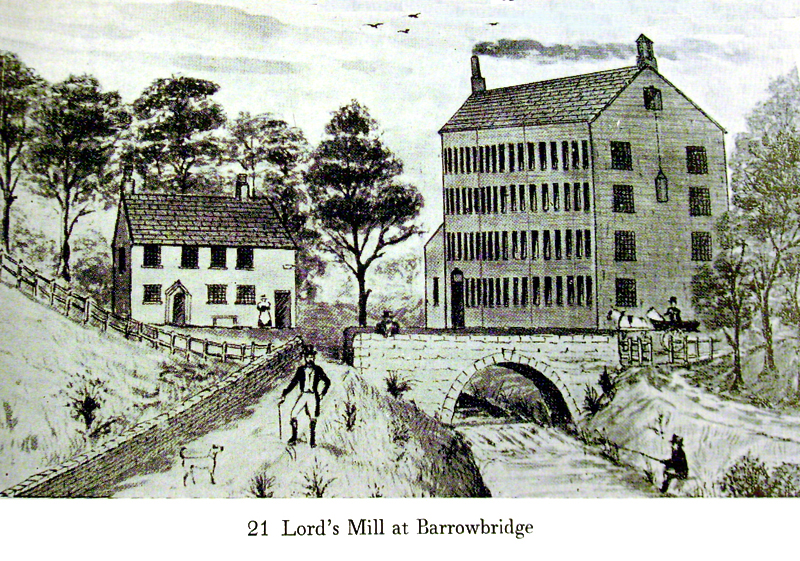

The equipment used in the cloth industry (yarn spinning

and looms) originally were powered by single persons.

Then trapiches (horses, typically a single horse) were

used (one horse power). These were followed by water mills

and finally by steam engines (the first useful steam

engine, by Watt, was 10 horse power). The steam engines

were constructed of iron and brick, and were powered by

coal. Thus, the coal and iron mines were the sources of

power for the Industrial Revolution. Hence the relevance

of this discussion of the coal and iron industry. In

addition to power sources, social problems such as riots,

workers' rights, gender discrimination, exploitation of

children, strike-breaking, immigration, industrial diseases,

etc., arose at this time. The agricultural sector was

unsettled as well; for example, the potato famine in

Ireland, the "Scotch cattle", and the "Captain Swing"

disturbances (repression by wealthy farmers of landless

agricultural workers, resulting in revolts by landless workers).

This is described by Charles Dickens in

"Martin Chuzzlewit": "Oh, magistrates, so rare a country

gentleman and brave a squire, had you no duty to society

before the ricks were blazing and the mobs were made?").

Protests against the displacement of laborers caused by the

spinning machinery at Richard Arkwright's mill took place.

Similarly, the Luddites (followers of "King Lud", or "General

Ludd") opposed the use of machinery, specifically the use of

jenny spinning frames. "General Ludd's" (Ned Ludd) followers

(the "Army of Redressers") were from cloth manufacturing

towns of Lancashire, Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire

and Cheshire. They were the stockingers or framework

knitters, and the shearsmen or croppers. These organized

bands broke spinning jennies because specialized, more

highly-paid laborers were replaced by low-skilled and

low-paid laborers, unapprenticed workers. One such riot took

place at Ottiwell's Mill in 1812 (located very near

Huddersfield, between Manchester and Yorkshire). As a

consequence, the "Frame Breaking Act" of 1812 was

specifically designed by the government of Spencer Perceval

to stop these violent labour protests. Violation of the

"Frame Breaking Act" was made a capital crime. The

government had to station 12,000 troops in the North of

England to suppress the Luddites, several Luddites being

executed, several transported.

Just as with the mill workers in the cloth industry, workers

in the coal and iron mines were malnourished, and worked in

cramped quarters for excessively long hours. This resulted

in people with stunted stature and bodies with pathological

posture and other medical problems. Puberty was delayed for

both boy and girl workers. Pelvic deformities among girl

workers caused difficult or fatal child-bearing. Just as

with clothing mill operatives, the coal and iron mines had

a very large number of children and women workers. Lung and

heart diseases were common, and life spans were greatly

shortened. In the cloth industry, the smaller hands of

children and women made working with the yarn and looms

easier, making them preferred workers over teen-aged

boys and men. Children and women could be paid less than men,

and also had very few legal rights in Victorian England

compared to men. The increasing employment of children and

women depressed the wages paid to teen-aged boys and men,

and also weakened the structure of the family. In the case

of the coal and iron mining industires, the smaller size of

children and women made it easier for them to fit into very

small mine shafts. As with the cloth industry, children and

women in the coal and iron mining industries became preferred

workers. This depressed the wages paid to teen-aged boys

and men who worked in the mines. This helped create a form of

"class" warfare between men and women, referred to as "gender"

discrimination, now.

Children as young as three years old commonly worked in the

mines. Young Welsh girls were also doorkeepers and carriers

of tools. Sometimes miners got an extra allowance for taking

down a young girl. Women and children pushed and pulled tubs

of coal through the small shafts, up inclines, through water,

to the horse paths. (Note that tubs did not have wheels;

"wains",

which were used later, did.) The women and children were

fastened to the tubs by a harness and chain. The shafts were

so low that working men had to lie on their sides while

loosening the coal with a pick, resting upon an elbow or

knee as a pivot, thus causing inflammations to these

joints. As hydrocarbon gases often caused explosions

or suffocation, the youngest children were assigned to

close doors when gas explosions occurred. Mine owners

commanded that workers use "Davy lamps" to reduce

explosions, but these lamps provided insufficient light,

thus miners used candles (the miners were blamed when

explosions occurred). Due to the heat in the mines,

workers of both sexes were often totally naked.

Work was typically done in 12-hour shifts, but often these

shifts were extended to 24 and 36 hours in length, and

night work was common. Although the standard of living was

relatively good, the working conditions were obviously

horrific. The government's Children's Employment Commission

report by Commissioner Mitchell states "...that children

often throw themselves down on the stone hearth or the

floor as soon as they reach home, fall asleep at once

without being able to take a bite of food, and have to be

washed and put to bed while asleep; it even happens that

they lie down on the way home, and are found by

their parents late at night asleep on the road."

Before the advent of screening plants, coal was

tipped and piled into a heap

to be loaded into wagons. In Lancashire and Yorkshire,

the miners gave it a primary riddling or sieving underground.

In Pembrokeshire this job was done by women. The coal was

also sorted by riddling at the surface, using hand-riddles or a

large stationary riddle. Before the miners were allowed to

appoint their own check-weigher in 1860, the management was

free to calculate a miner's payment by measure. A miner's

work was identified by a tin tally and only the tallies that

came up on the full tubs of coal were counted. The miner therefore

had no say in whether a tub was full or what constituted good

coal. At many pits a girl shouted out when the tub had some

dirt, thereby enabling the banksmen to know whether to penalize

the miner. The appointment of the miner's own check-weigher

and the system of payment by weight also involved the use of females.

After the full tub was run to the landing, the women helped place it

on a swivel or turntable, where it would be weighed and then run

along rails or landing plates to the tippler. In 1873 Arthur

Munby, an educated observer who sympathized with the class of

proletarian women2, noticed

the huts for the new tally-takers (known as the

in the Wigan area).

These girls shouted out the miner's tally number and collected

the tallies.

Women also helped to operate the tipplers, which teamed or tipped the

coal onto the screen. The "kickup" type was shaped like an iron cradle

and when the full tub of coal ran into this cradle, its weight caused

it to over-balance and tip out the coal. It automatically righted itself

and the tub was returned to the shaft. A trap door at the bottom of the

chutes prevented the coal from sliding onto the screen until it was

needed.

The main task for women was to work as drawers

(also called barrowmen,

carters,

draggers, hauliers,

hurriers or putters).

This involved pulling sledges, tubs or wains

along the hard floor, or on wet clay or on planks, from the coal face

to the bottom of the shaft. Women worked as bearers,

fillers, hookers of baskets, cleaners and as horse drivers. Whole

collier and salter families were bound as slaves in servitude to

employers, lacking any real freedom. Binding workers was originally

designed to cope with a shortage of labor during the expansion of

the coal and salt trade. However, binding the workers amounted to

appropriating them as property; this soon resulted in binding

entire families for life. It ensured that "wives, daughters and

sons went on from generation to generation under the system, which was

the family doom". The hewer who extracted the coal from the pit face

generally engaged two bearers and perhaps shared a third

'fremit' (non-relative) with a fellow

hewer. By the 17th century some pits had primitive windlasses known

locally as a 'druke and beam'.

The 1842 report described women using windlasses above and below the

ground. The considerable depth of some pits meant that windlasses

were used to haul tubs up steep slopes, a number being fixed at

convenient intervals on the incline of the coal or iron vein. Women

would turn the handles of the windlasses' wooden rollers. This

system of using windlasses in this manner was used in what was

called 'pitching veins'. They also

helped with a pouncing or boring when a new shaft was being sunk.

The introduction of horses and a few wheeled vehicles in the

mid-18th century saw boys taking over haulers' jobs. This meant

that in the more advanced pits drawers now only had to pull the

coal down the passages as far as the main roadways. It was then

transferred to four-wheeled trams running on wooden rails. The

trams were pulled by horses and guided by

trammers, or horse-drivers.

In the mid-1770's cast-iron rails were introduced in place

of wooden ones.

Yorkshire females hurried an average of 20-24

corves and multiple

rakes

over distances of over 200 yards each way. Some Scottish

strappers drew

hutchies but where there were no

rails they pulled slypes.

Female pumpers found their workplaces so wet that they had to be

relieved every six hours. Others carried buckets of water

or helped red (clean) the roadways at night. Margaret Leveston

(66 years old) did 10 and 14 rakes there. Girls might begin

separating coal from culm on the

surface but by age 12 would graduate to windlass work below

ground.

Women also worked in the wagons with big spades, helping to

control the flow of coal in the chutes; they also trimmed, or

leveled down, the coal in the wagon. Females took

drams from the top of the pit and

'tripped' them down the screen. Sometimes sorters worked at

the screens.

'Poll girls' took iron ore from

trams, sorted out stone and shale, cleaned the ore and piled

it ready for the furnaces;

'coke girls' stacked coal ready

for coking or broke limestone with hammers ready for

smelting. 'Pilers' worked in the

puddling mills, stacking and weighing

the heavy iron bars which had been cut to be made into rails.

By the early 19th century shallow pits were using endless

chain systems with windlasses, winding the deeper pits with winding

engines that used hemp ropes. These were replaced by both

flat and round wire cables. In Scotland at a few Pembrokeshire

pits, coal was still being carried on the backs of women coal

bearers. Both miners and coal were frequently drawn up to the

surface by hand. In Shropshire, women helped attach baskets to

ropes and wound them up and down the shaft by hand.

Some windlasses had been adapted to be worked by horses. For

example, the cog and rung gin was

a windlass that worked on a wheel-and-pinion basis.

The horse-driven whim gin, or

whimsey, now superseded the cog and

rung. The whim gin was comprised of a drum that was mounted on a

vertical shaft away from the pit mouth, whose diameter could be

increased to provide faster winding. The number of levers and

horses could be increased for heavier winds.

Arthur Munby (an important observer) described the mid-century

banking method: as the cage reached

the top of the shaft, women helped to push a slide underneath

and unloaded the wains

(skips tubs) and pushed them along

the pit bank. They also helped to 'run them in', which meant

pushing the empty wains back into the cage. In South

Wales, where an abundant supply of water existed,

horse gins were replaced by balance

pits. Full trams were raised by lowering empties containing water

and thereby acting as a balance (the horse was replaced by gravity).

The speed at which iron and coal ore could be raised to the surface

depended upon how quickly water could be drained from the container.

Balance pits were introduced in the Tredegir area in 1829. Ty Trist

mine was started as a balance pit in 1834, changing to steam winding

in the 1860's. (Steam winding was faster than draining water.)

The working environment of the Iron miners differed

little from that of the coal miners and the cloth

factories: industrial slavery. One notable

difference was that the Irish formed the predominant

work force in iron mining.

Both the "truck" (company store) and "cottage" (company

housing) systems were effectively universal. Miners were

paid by volume though coal was sold by weight. In

addition, miners were fined if the tubs credited to them

contained coal-dust or were only partly filled (though

over-filled tubs were not paid any extra). When workers

were paid by weight, false scales were used. Miners' pay

was delayed, thereby enslaving the miners. Any complaints

were heard by local Justices of the Peace who were almost

universally mine owners themselves. In most cases, miners

were bound by a contract to work for a year, during which

time the miner could not work for any other employer.

However, the mine owner was not obligated to provide

employment. If a contracted miner worked elsewhere (in

violation of the contract), then the miner was imprisoned

or dismissed.

The situation of mine workers was immediately

remedied (Lord Ashley's Children's Employment Commission

1842), but only on paper, as no mine inspectors

were appointed to effect any changes. Instead, the

miners held a conference in Manchester in March, 1844

and formed a union and demanded:

The mine owners refused, and a great strike took place

in 1844. Using the cottage system,

the miners were thrown out of their houses,

miners were falsely arrested, coal was imported to

Newcastle (!) so that the mines could fulfill their

contracts, and the mine owners employed

"knobsticks" (scabs, but when

Irish, these strike breakers were called

"blacklegs"). After several

months the union funds used to support striking workers

were consumed and the strike broken.

W. P Roberts was an important

defense solicitor.

Friedrich Engels pointed out that if the views of

Malthus were accepted, then "[T]he proletariat would

increase in geometrical proportion...and the

proletariat would soon embrace the whole nation,

with the exception of a few millionaires. But in

this development there comes a stage at which the

proletariat perceives how easily the existing power

may be overthrown, and then follows a revolution."

The expectation of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

was that industrialization with its proletariat would

spread throughout the globe would result in a

proletariat with class interests that surmounted

national borders as well as cultural differences;

thus, the proletariat class interests were not

national, but international.

This description is based upon Engels, chapter "The

Mining Proletariat", pp. 247-262, Penguin, 2005 edition.

* The 1842 Report of the Children's Employment Commission discussed not only the collieries, but also discussed pottery factories. Some major points to be noted include the following:

© Copyright 2006 - 2019

The Esther M. Zimmer Lederberg Trust

Web Site Terms of Use

Web Site Terms of Use